- xiii -

In this country critics only make themselves known in tandem with the writers who have inspired them. Belinskij made his appearance … on the basis of Gogol′ … Grigro′ev came out writing about Ostrovskij… With you, it is a direct and boundless feeling for Lev Tolstoy, ever since I have known you.

— From Dostoevsky′s letter to Strakhov, 26 February 1869

He [Strakhov] had an extraordinary love for this man [Tolstoy]. To Nikolaj Danilevskij he was bound as to a luminary embodying all the traits of the [Russian] people: a clear mind and a firm, open character; to Apollon Grigor′ev as to an initiator of proper practices in his favourite occupation, [literary] criticism. His allegiance to Tolstoy went deeper, into the mystical: he loved him as the embodiment of the deepest and best aspirations of the human soul, as a special nerve in the huge body of mankind, in which the rest of us make up the less understanding and less significant parts; he loved him precisely because of his intangibility and incompleteness… He loved that dark abyss in him with no bottom to be seen, from the depths of which many treasures were still to arise. A better friend Tolstoy never lost, there can be no doubt.

— From V. V. Rozanov′s eulogy (Pamjati usopshikh) to Strakhov, 1896

Leo Tolstoy and Nikolaj Strakhov:

a personal and literary dialogueNikolaj Nikolaevich Strakhov was born in 1828, the same year as his great friend Leo (Lev Nikolaevich) Tolstoy and his great adversary Nikolaj Chernyshevskij. His adult life spans almost the entire second half of the century. Personally close to several literary giants of his period — Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, Afanasij Fet, Vasilij Rozanov and Vladimir Solov′ev —, Strakhov was involved in most of the major intellectual controversies of his time. He was well known to (even if not widely appreciated by) the contemporary Russian intellectual élite, not only as a translator of European philosophical works but also as a literary critic and a philosophical writer in his own right. He was especially close to Tolstoy, with whom he collaborated for many years as a literary / editorial associate and concerning whose works he penned a number of important articles. In 1872 Strakhov supervised the publication of Tolstoy′s Azbuka [A Primer]. He later took charge of the proofreading and printing of Anna Karenina and multiple editions of Tolstoy′s individual and collected works, often in collaboration with Tolstoy′s wife, Sofia Andreevna Tolstaja.

- xiv -

His reputation among his Russian contemporaries notwithstanding, Strakhov remains a little known quantity in the eyes of present-day world scholarship. A particularly rich yet largely untapped resource for shedding light on his critical articles, memoirs and published commentaries, is the vast number of letters he wrote both to and about the literary figures he counted among his acquaintances — especially (in terms of both quantity and depth of insight) Leo Tolstoy. Many of his letters to Tolstoy could be considered critical articles in themselves, presenting a fascinating discourse on literature, journalism, art and other cultural phenomena in both Russian and Western European society, past and present.

The letters also offer penetrating insights into the character of Strakhov himself, revealing him as a profound and subtle thinker, an historian-philosopher, who regarded literature as a mirror reflecting the moral condition of society as a whole. We learn of his own poor health as well as his compassion for others in bodily distress, and his grief at the frequent passing of friends and acquaintances. We discover the special bond he felt with the Tolstoys and their family, and his willingness to go to almost any lengths to look after their needs as he perceived them. More than just another visitor at Yasnaya Polyana, more than even a capable editorial associate, Strakhov fulfilled Tolstoy′s deep need for a close friend and confidant, a sounding-board on whom he could rely for an honest, clear-sighted and meaningful appraisal of his own work. Unlike the majority of Tolstoy′s followers, Strakhov succeeded in maintaining an objective distance from his mentor, and this enabled him to significantly contribute to Tolstoy′s elucidation of his own ideas. Even while sincerely appreciating the latter′s genius as a writer, he was able to respond intelligently to these ideas from an independent perspective; on occasion this even meant arguing with Tolstoy as an equal.

A consecutive reading of the letters as a unified whole elucidates the progressive development of the ideas and motifs which they held in common and which guided the two men′s lives, including many of the basic underpinnings of Tolstoy′s thought both before and after his spiritual ′conversion′ in 1880. In fact, the germ of almost all the moral/religious principles he expounded in the last three decades of his life can be found in his pre-1880 letters to Strakhov — his pacifism, rejection of capital punishment, his hostility toward both state bureaucracy and excessive urbanisation. In relative seclusion at his Yasnaya Polyana estate, Tolstoy′s need for serious intellectual contact with erudite scholars was satisfied in great part by his relationship with Strakhov, who was both qualified and eager to be of service. Witness Tolstoy′s letter to Strakhov (Nº 115) of 26 April 1876 expressing his great joy at the insight and understanding displayed in Strakhov′s analysis of his work. In a subsequent letter (Nº 208, dated 23 November 1878) he told Strakhov: ″When I awake, the first thing that comes to mind is my desire to communicate

- xv -

with you″. And in a letter to P. A. Sergeenko (13 February 1906), Tolstoy referred to Strakhov as one of three people (in addition to Sergej Semenovich Urusov and his aunt Aleksandra Andreevna Tolstaja) to whom he ″had written many letters″ and whom he deemed ″interesting to those who are interested in me as a person″ (Sergeenko 1910). The letters also offer extensive information about the major writings both men were producing between 1870 and 1896; they serve to clarify not only their objectives and background but also the practical procedures involved in their publication.

It is surprising, in view of the above, that so little critical study has been carried out to date on Strakhov′s life and works, particularly of the pivotal role he played in his literary association with both Dostoevsky and Tolstoy. While the Strakhov-Dostoevsky letters1 have received some documentation by A. S. Dolinin (1928—59), there have been no sustained studies examining Strakhov′s involvement and correspondence with his contemporaries, either in Russia or in the West; this is especially astonishing in the case of Tolstoy.

A few pre-1917 studies on Strakhov are relevant and will be taken into account in the critical appraisal of the relationship between Tolstoy and Strakhov on which I am currently working (and which will contribute a third volume to this collection):

• V. Rozanov, ″Literaturnaja lichnost′ Strakhova″ [A Literary portrait of Strakhov] (1890), and the obituary (″Pamjati usopshikh″) he wrote in 1896, amounting to a thirty-page critical appraisal of Strakhov′s works.

• B. Nikol′skij, ″N. N. Strakhov. Kritiko-biograficheskij ocherk″ [N. N. Strakhov: A critical and biographical sketch] (1896) — a succinct account of Strakhov′s career.

- xvi -

• V. Lazurskij, ″L. N. Tolstoj i N. N. Strakhov: iz lichnykh vospominanij″ [L. N. Tolstoy and N. N. Strakhov: from personal reminiscences] (1910) — a description of Strakhov′s visits to Yasnaya Polyana and his warm relationship with the whole Tolstoy family.

• V. Kranikhfel′d, ″L. N. Tolstoj i N. N. Strakhov v ikh perepiske″ [L. N. Tolstoy and N. N. Strakhov in their correspondence] (1912) — an article, based on a very limited number of letters, dealing mainly with Strakhov′s adulation of Tolstoy.2

While Strakhov was largely neglected by Soviet scholarship (probably because of his ultra-conservative nationalist views), several references from this period will be useful to the proposed study:

• B. Bursov′s discussion of Strakhov′s relationship with Dostoevsky in Problema zhanra v istorii russkoj literatury [The Problem of genre in the history of Russian literature] (1969), discussing Strakhov′s ″antipathy and unjust criticism″ of Dostoevsky expressed in his letters to Tolstoy; he later revised this discussion into an article entitled ″U svezhej mogily Dostoevskogo: Perepiska L. N. Tolstogo s N. N. Strakhovym″ [At Dostoevsky′s fresh gravesite: L. N. Tolstoy′s correspondence with N. N. Strakhov] for his 1974 volume Lichnost′ Dostoevskogo [A Portrait of Dostoevsky].

• U. Gural′nik, ″N. N. Strakhov — literaturnyj kritik″ [N. N. Strakhov — literary critic] (1972).

• N. Skatov, ″Kritika Nikolaja Strakhova i nekotorye voprosy russkoj literatury XIX veka″ [Nikolaj Strakhov as critic and certain questions on 19th-century Russian literature] (1982) — a substantive article positing several cogent arguments as to why Strakhov′s philosophical works were unacceptable to his contemporaries, together with a survey of Strakhov′s assessment of writers such as Pushkin, Gogol′, Turgenev, Dostoevsky and Tolstoy.

Western scholarship is marked by a similar dearth of materials on Strakhov. There are a few works that deserve mention, however:

• L. Gerstein, Nikolaj Strakhov (1971) — a detailed analysis of several of his major works in a historical perspective.

• C. J. G. Turner, A Karenina companion (1973), particularly his summary of Strakhov′s ideas on Darwinism.

• B. Sorokin, ″Moral regeneration: N. N. Strakhov′s ′organic′ critiques of War and peace″ (1976) — which includes a useful description of Apollon Grigor′ev′s influence on Strakhov.

• D. Orwin, Tolstoy′s art and thought 1847—80 (1993) — including a brief discussion of Strakhov′s views of Tolstoy′s works; of particular interest is

- xvii -

her more recent ″Psikhologija very v Anne Kareninoj i v Brat′jakh Karamazovykh″ [Psychology of religion in Anna Karenina and The Brothers Karamazov] (2000), which compares Dostoevsky′s and Tolstoy′s use of Strakhov′s ideas in their respective novels.

The relationship was initiated after Tolstoy happened to read Strakhov′s journal articles, which included reviews of Tolstoy′s own works. One in particular prompted Tolstoy to write a letter to Strakhov in 1870. The following year they met in person,3 and became not only working colleagues but also close friends — a friendship that eventually extended to the entire Tolstoy household as a result of Strakhov′s frequent and lengthy stays at Yasnaya Polyana.4

- xviii -

Like her husband, Sofia Andreevna had great respect for Strakhov′s intellect and integrity and valued his opinion. Her appreciation for the importance of Strakhov′s contribution to the Tolstoys′ work is, perhaps, best illustrated in her own words from her letter of 20 February 1893:5

It is impossible to get assistants anywhere in this world. They are sent by destiny … as God has sent you to me — an unselfish and industrious person, and, above all, a clever genius.

This might be considered as flattery, were it not that the whole tone of their correspondence indicates completely the opposite — namely, a genuine and unequivocal respect for this brilliant if self-effacing friend and editorial associate.

The respect, which was mutually shared, continued on a high level throughout their relationship, and neither party ever permitted it to slip into casual familiarity, although a certain degree of friendliness is definitely present. Indeed, their close personal friendship is evident right in some of their early letters (see letters of 4 May 1876 and 9 January 1877), where Sofia Andreevna does not hesitate to ask Strakhov personal favours such as lending money to a visiting Englishwoman or making an appointment for her with her Petersburg physician. Their friendly collaboration on editions of Tolstoy′s works is indicated in Strakhov′s letter of 24 September 1893, which opens with the following paragraph:6

I humbly thank you for sending the new edition [of Tolstoy′s Collected works]; I was waiting for this favour, and it arrived at the very moment I was looking forward to it. A marvellous edition! I tried to find some mistakes, but didn′t find any. What is especially exciting for me is that all my labour has been accepted and reflected in these pages. I swear to you that I had not great hopes for that. With the energy you have, it seemed to me you would spare no effort to exercise some control of your own. And yet you did everything exactly as I had indicated. I am very happy about that! After all, I was endeavouring to do my very best, in my labour of love over these precious writings. You understood that, you accepted it, and I thank you from the bottom of my heart.

The mutual exchange in its entirety is not only engaging to read but must be taken into account when dealing with any of their individual authors, and especially with Tolstoy′s works — the principal focus of their concerns.

- xix -

Some critics7 rightly point out that Strakhov′s relationship to Tolstoy bordered on adulation. Indeed, his loyalty to his mentor permeates all his letters to Tolstoy as well as those to some of his other correspondents.8

***

Strakhov was a highly educated man. Having studied divinity at a seminary and the natural sciences at university, he was eminently knowledgeable in philosophy and literature.9 Following a teaching career in mathematics and natural sciences in Odessa and later in St-Petersburg, he became a librarian at the St-Petersburg Public Library, a post he continued to hold until his retirement in 1885. He never married.

His first published work of note was Letters on organic life (1858) — a book focusing on the pre-conditions of development which make life more than just a response to external stimuli and turn it into something capable of transcending the very environment which is said to influence it. Such a potential, he suggested, constitutes the very essence of living. This publication led to Strakhov′s collaboration with a prominent critic of the day, Apollon Grigor′ev (1822—1864),10 in the co-editing of Dostoevsky′s journal Vremja.11 Dostoevsky was favourably impressed by Grigor′ev′s ideas, describing him and his followers as pochvenniki — ′people rooted in the soil′ of Russian national life. After Grigor′ev′s untimely death in 1864, Strakhov went on to spread the ideas of the pochvenniki movement in his own publications,12 warning again and again on the perils of Darwinism and materialism. He considered both Slavophilism and Westernism inadequate for the proper development of Russian literature and philosophy, and saw in Tolstoy′s writings (along with those

- xx -

of playwright Aleksandr Ostrovskij) an antidote to the negative and ironical views of Russian life promulgated by Gogol′ and others.13

Strakhov was also captivated by Tolstoy′s sheer genius, which he first discovered in the 1860s when he undertook a critical analysis of War and peace.14 He also discovered many of Tolstoy′s ideas to be very close to his own, especially in respect to the integrity of the individual, the rejection of evil and the striving for good. Tolstoy was more than a mentor for Strakhov — he became his inspiration, his foundation-stone, so to speak.15

Tolstoy in turn found in Strakhov, a man whose broad range of interests turned him into an avid reader of newspapers and magazines in a variety of languages, a significant source of information about the outside

- xxi -

world, as well as a reserve of intellect and understanding oriented in a similar direction to his own — one that could serve as a sounding-board for his ideas and help him hone their exposition in his publications.

But their relationship went beyond the intellectual. Over the years Tolstoy became extremely fond of Strakhov, as is evident from their whole correspondence and references to Strakhov′s much-desired visits to the Tolstoy home. Strakhov′s portrait is to be found in Tolstoy′s study along with those of a very few others he considered close friends. Strakhov is named in Tolstoy′s first will as one of the executors entrusted with the task of examining and sorting the writer′s numerous papers.16

A biography of Strakhov has yet to be written. Material for such a biography is lying in abundance in archives in Moscow, St-Petersburg and especially Kiev — material that includes Strakhov′s fictional writings, his correspondence with Russian and foreign authors, critics and publishers, as well as his evaluations of submissions for the Pushkin literary prize, as commissioned by the Russian Academy of Sciences. The appendix to the present publication includes a series of biographical notes penned by Boris Nikol′skij pertinent to the influences on Strakhov in his early years (although written more than a century ago, this material is still the most useful to date). Another helpful work is Marina Shcherbakova′s article (2002) ″Stranitsy junosheskogo dnevnika N. N. Strakhova″ [Pages of N. N. Strakhov′s youth diary]. It reveals an extremely intelligent, philosophical

- xxii -

and observant young man, given to thorough analysis and a writer of extraordinary mental clarity.

Strakhov published some ten articles on Tolstoy (although sadly he left no personal reminiscences of his mentor, as he did in the case of Dostoevsky, with whom he also collaborated for a long period of time). These articles, almost all of them published in N. N. Strakhov, Kriticheskie stat′i ob I. S. Turgeneve i L. N. Tolstom [Critical articles on I. S. Turgenev and L. N. Tolstoy] (2nd ed., St-Petersburg, 1887: 145— 387), include the following: ″Sochinenija gr. L. N. Tolstogo 1864″ (a review of Tolstoy′s collected works published in Otechestvennye zapiski [1866]); two articles on Vols. 1—4 of War and peace and one on Vols. 5—6, all published in Zarja (1869—70); ″Literaturnaja novost′″ [Literary news] (Zarja, 1869); ″Neskol′ko slov k predydushchim stat′jam″ [A Few words on the preceding articles] (Zarja, 1871); ″Obuchenie naroda (O narodnom obrazovanii)″ [Public education] (Grazhdanin, 1874); an article on Tolstoy′s Chem ljudi zhivy [What people live by] (Grazhdanin, 1882); ″Vzgljad na tekushchuju literaturu (Ob «Anne Kareninoj»)″ [A Look at current literature: about Anna Karenina] (Rus′, 1883); ″Frantsuzskaja stat′ja o gr. L. N. Tolstom″ [A French article on Count L. N. Tolstoy] (Rus′, 1885).

These articles are interesting both from the historical point of view and from their pertinence to Tolstoy studies today. In the first place, his solid reputation as a literary critic was well documented by his contemporaries, although perhaps the qualities entitling him to that reputation are most evident in his own words, taken from a preface to a separate publication of his articles on War and peace.17 With a deserved sense of self-satisfaction he described his approach to criticism as follows:

…I followed the correct and proper path. I did not quarrel with the artist, I did not hasten to cast myself in the role of his judge, I felt no inclination to contradict his individual opinions and put forth my own as if they were more important than his. Above all I endeavoured to comprehend the artist′s consciousness, to delve into the sense of delight that had captured me so powerfully and compellingly, to understand where such power came from and what it was made of.

Indeed, Strakhov was one of the few critics who not only had a high estimate of War and peace, but had an immediate understanding of its tremendous historical significance for the world.

The significance of Strakhov′s insight, too, has by no means lessened over time. Today′s Tolstoy experts can find in Strakhov′s articles an abundance of food for thought and new prospects for literary analysis. In the first place there is the discussion of the infantile consciousness displayed by the characters of Tolstoy′s early works, whose ″soul … is

- xxiii -

immature″,18 along with the opportunity for comparison along this line with his later works. Then there is the comparative analysis of War and peace with Pushkin′s Kapitanskaja dochka [The Captain′s daughter], bound by the common genre of the family chronicle.19 Apollon Grigor′ev′s notion of ″meek and predatory types″20 is both interesting in itself and in relation to the images created by Tolstoy. While it is known that Tolstoy was not fond of this notion (see his letter [Nº 104] to Strakhov of 1…2 January 1876), no one has ever offered either a rational counter-argument to Grigor′ev′s ideas on the whole or an analysis of Tolstoy′s attitude to them in particular.

***

It will be useful to examine, however briefly, Strakhov′s ideas expressed in the publication which initiated their life-long friendship and working relationship, namely his articles on Tolstoy′s War and peace, all appearing in Zarja in 1869 and early 1870. Tolstoy considered them most intelligent — rare praise, indeed, given his well-known aversion to critics. The summary given below is characteristic of the views Strakhov held all his life.

Article I (on War and peace, Volumes 1—4)

The first of these articles deals with the fascination of many contemporary writers with the idea of progress — which was being achieved, Strakhov believed, only at the expense of losing sight of valuable historical lessons and losing ″the unchanging, eternal characteristics of the human soul″ (217).

It was against this frame of reference that Strakhov formulated a series of strident — and, one may say, controversial — observations on War and peace. His introductory section (pp. 179—86) comprised for the most part a condemnation of contemporary nihilists who denied the value of historical study. Strakhov, on the other hand, saw War and peace as ″not an historical novel at all″ — i. e. not a novel ″aimed at uniting the interests of history and fiction″ (187), but rather a deeply philosophical work about the nature of humanity for which history served as a canvas for an artistic expression of this philosophy, wherein scenes and events are described largely ″through the impressions of their participants″ (189). In answer to criticism of the novel for its negative portrayal of Russian society, he emphasised his view that this had been done not for the sake of mere exposé, but to present a multi-faceted and historically accurate picture of this society (193), and considered Tolstoy not so much a ′realist

- xxiv -

exposer′ or a ′realist photographer′ as a ′realist psychologist′ (195), whose goal was to search ″in every character depicted for that divine spark which constitutes individual human dignity″ (196).

One of Tolstoy′s means of achieving this goal, according to Strakhov, was to ″discover their human foundation, to show the people behind the heroes″ (205), and to portray his heroes in a variety of emotional states. To this end, Tolstoy depicted each human emotion ″not in the form of some kind of invariable quantity, but only as the capacity for a certain feeling — as a spark which is constantly smouldering, ready to burst into flame, … but which is all to often smothered by other feelings″ (207). Here it may be seen that Strakhov was unwittingly foreshadowing the psychological analysis which would come to characterise Tolstoyan studies later in the twentieth century. For him the whole novel was an exploration of ″the hidden depths of life″ (216), which was ultimately responsible for the book′s ″universal human appeal″ (217) and ensuring it both a world-wide and long-lasting popularity. In fact, it was Strakhov′s strong focus on War and peace as a work of profound philosophy rather than simply an historical narrative or family chronicle that ensured his own prominent place in the history of Russian literary criticism.

Article II (on War and peace, Volumes 1—4)

Strakhov′s second article delves into the ′family-chronicle′ aspect of the novel, comparing it with Pushkin′s The Captain′s daughter (223—24), pointing out that both novels focused on real Russian households (263), and the ″collision of private life with public″ (263—64).21 He spends a good part of the article, in fact, discussing critics Apollon Grigor′ev and Vissarion Belinskij′s views on Pushkin. He does, however, eventually return to War and peace, which he describes as a culmination of a single, continuous chain of the author′s literary expression. He makes frequent reference to Grigor′ev′s close acquaintance with Tolstoy′s earlier writings, which he considered simply ″études, sketches and practice attempts″ (250) by comparison, but they share with the novel a constant endeavour to portray the inner struggles of human existence (251), as well as ″a denial of anything contrived or superficial in our development″ (251). In particular, Strakhov sees War and peace as a confirmation that ″the measuring-rod of good and evil″, which Tolstoy had earlier written about in Lucerne, was ″within the complete grasp of the artist, who confidently uses it to measure any fact that happens to come to his mind″ (261). His division of the novel′s characters into ″meek and

- xxv -

predatory types″, was subsequently rejected by Tolstoy as irrelevant,22 although Strakhov himself noted that certain characters (notably the Bolkonsky father and son, as well as Natasha and Pierre) transcended any attempt at such a simple classification.

Article IV (On the appearance of Volume V of War and peace)

Strakhov took this opportunity to praise War and peace as a ″work of genius″ (269), adding that ″Russian literature can add one more to its storehouse of great writers″ (270). He was especially struck by the depiction of Platon Karataev (270), whom he considered a most significant symbol tying together the strands running through the whole novel.

Article V (On Volumes V and VI of War and peace)

Strakhov begins this article by calling War and peace a masterpiece characterised by a fully-formed vision, a work of irreproachable quality, completely devoid of ″any major imperfection″ or ″anything that could take away from complete pleasure, or diminish our ecstasy″ (272). In it, he says, Tolstoy ″had overcome in his soul the process of denial and, having freed himself from it, began to create images embodying the positive aspects of Russian life″ (283) and echoes Grigor′ev′s declaration that Tolstoy′s is ″a voice for the simple and good against the false and predatory″ (284). Finding the novel to espouse philosophical and æsthetic concepts not unlike his own, he risks losing a certain degree of objectivity in sympathetically accepting Tolstoy′s idea that ″history is made in spite of human randomness″. He does, however, find that many of the ″dry rationalisations″ (295) of the novel′s Epilogue are inappropriate in works of fiction.

Article IX (on Anna Karenina)

While there is not sufficient room here to comment on all Strakhov′s articles on Tolstoy, his discussion of the author′s other major novel, Anna Karenina, is especially significant to an understanding of Strakhov′s own world-view. While much of this discussion may be found in the correspondence in the present volumes, it is also worth taking note of his brief 1883 article (IX) ″Vzgljad na tekushchuju literaturu (Ob «Anne Kareninoj»)″ [A Look at current literature (On Anna Karenina)].

A theme permeating Strakhov′s reflections on Anna Karenina is the ideological struggle between ′Russian ideas′ and the ′Western ideas′, and the tendency of his contemporaries to get carried away with a simplistic and exaggerated confidence in the latter (341—42).

- xxvi -

He then proceeds to discuss ″the spiritual mentality of our educated classes″ (348) through a comparison of Anna Karenina with two other contemporary novels: Turgenev′s Nov′ [Virgin soil] and Dostoevsky′s Brat′ja Karamazovy [The Brothers Karamazov]. The former he faults for its forsaking of the fundamental goal of art to examine ″broader and deeper subjects″ than ″fortuitous and momentary″ happenings (354), whereas Anna Karenina, by contrast, ″takes up the eternal question of human life, and more than a single contemporary type and contemporary interest″ (361). On the other hand, Dostoevsky′s novel is found to share a good deal in common with Anna Karenina — for example, the focus on ″moral chaos″ (362) and the pointing to religion as the means of overcoming chaos and despair (365).23

In the case of Tolstoy′s novel, this is particularly noticeable in the character of Levin who, driven by despair, turns to religious ideas (361). Strakhov mentions this turning on more than one occasion, and describes Levin′s mental state as follows:

…the very thread of his life could at any moment break just as easily as a thin spider′s web. This was the reason behind his despair. If my life and joy were the only goal of my life, then such a goal would be so insignificant, frail and evidently unattainable as to inculcate only a sense of despair — it could never inspire one but only depress.

This statement may be compared with Strakhov′s reference in Article I to the infantile mentality exhibited by the characters of Tolstoy′s early works,24 who suffer from the impossibility of attaining their questionable ideals and so equate ′unattainable′ with ′unworthy′. While the article indeed begins with the polemic of ′Russian′ versus ′western′ ideas, by the end of the piece the polemic has become much more concretised into the conflict between religion and atheism.

Strakhov′s published comments on Anna Karenina may be viewed, with the help of the present correspondence, in the light of his direct involvement and assistance to Tolstoy in its editing and publication — a fact considerably less well-known, even to many Tolstoy scholars. One of the compilers′ annotations to the letters (Note 1 to Letter 174 of 20 January 1878) which is particularly pertinent to this point bears reproducing in English translation here. It comprises a memo Strakhov appended to the proofs of Anna Karenina he had collected after completing his korrektura for the first separate publication of the work. The memo reads as follows:

- xxvii -

This volume is the copy of Anna Karenina from which the separate edition of 1878 was printed. It consists of sheets torn from Russkij vestnik [Russian Herald] and includes corrections and changes in the author′s own hand. But since my own hand is discernible in this too, I feel obliged to explain.

In the summer of 1877 (June and July) I was visiting Lev Nikolaevich Tolstoy at Yasnaya Polyana, and suggested a review of Anna Karenina, with a view to preparing it for a separate edition. I set about a preliminary reading to correct punctuation and obvious errors, and to point out to Lev Nikolaevich places which for one reason or another seemed to be in need of improvement, mainly — almost exclusively, in fact — involving lack of clarity and incorrect use of language. Thus it came about that I did my reading and corrections first, and then Lev Nikolaevich did the same. It went on this way until half-way through the novel, but then Lev Nikolaevich got more and more involved in the work, overtook me, and I ended up doing my corrections after his. I would always take a look at his corrections first to make sure I had understood and interpreted [the text] in the right way, since afterward I would have to do the proofreading.

Each morning, after a full discussion over coffee (which was served at noon on the terrace), we would part and sit down to work on the tasks at hand. I would work in the study, downstairs. It was agreed that an hour or a half-hour before dinner (5 o′clock) we should set out for a walk to refresh ourselves and work up an appetite. As pleasant as the work was for me, I, with my customary accuracy, rarely missed the appointed time and, after getting ready myself for the outing, I would go to summon Lev Nikolaevich. He almost always took his time and sometimes it was difficult to tear him away from his work. In such cases signs of stress were all too evident: I would notice a rush of blood to the head, Lev Nikolaevich would be distracted and eat very little for dinner.

This was our daily routine for more than a month. The toilsome work bore its fruit. As much as I loved the novel in its original form, I was fairly quickly persuaded that Lev Nikolaevich′s corrections were always done with amazing mastery, that they illuminated and deepened characteristics which had seemed clear enough before, and invariably blended in with the tone and spirit of the whole work. In respect to my corrections, almost all concerning language, I noticed another peculiarity which, while it did not surprise me, was quite conspicuous. Lev Nikolaevich was firm in his insistence on even his least significant turn of expression and would not agree to even the most innocent changes. From his explanations I was persuaded that he had a particular fondness for his language and that in spite of any apparent brusqueness or unevenness of flow, he carefully considered each of his words, each turn of phrase, in the same way as the most sensitive poet.

Indeed, I always marvelled at how much he thought, how much his mind worked, it struck me as something new each time we met, and it is only by such an amplitude of soul and mind that the power of his works can be explained.

St-Petersburg, 18 April 1880.

Following Part VIII are to be found here four printer′s sheets containing the beginning of Anna Karenina. These sheets and the proofs which follow

- xxviii -

them are what remains of this first edition, which Lev Nikolaevich had in mind before he began running his novel in Russkij vestnik. The printing had begun in Moscow, and Jurij Fedorovich Samarin had undertaken to do the proofreading. But later — right at the beginning of 1875, if I am not mistaken, Lev Nikolaevich approached me to take over the proofreading. Everything stopped, however, with the fifth sheet.

N. Strakhov

St-Petersburg, 18 September 1880

***

As Christian (1978: 227) points out, during the 1870s Strakhov became Tolstoy′s principal correspondent, taking over this honour from the poet Fet (Afanasij Afanas′evich Shenshin).25 In a letter to Strakhov of 15 February 1876 Tolstoy demanded his correspondent write him long and substantive letters; a few months later (26 April) he expressed his great joy at the insight and understanding displayed in Strakhov′s analysis of his work. At one point (13 November 1876) he called Strakhov ″my true friend″ [svoim istinnym drugom], and in yet another letter (16 November 1880) he enjoined his friend not to get involved with anyone else′s work, but to ″write only to me and converse [only] with me″. Tolstoy once referred to his correspondence with Strakhov as a most important documentation of his spiritual growth.

The present collection, consisting of 467 letters (each writer contributing approximately half the number), represents a gold-mine of information and wisdom.26 Its contents deal with literature, philosophy, religion, ethics, politics and personal life. It is the culmination of a number of partial collections of their correspondence, beginning in 1893, during Strakhov′s lifetime,27 when the latter′s acquaintances would make hand-written copies of Tolstoy′s letters to him — notably the writer Aleksandr Modestovich Khir′jakov. These copies ended up in the archives held by Vladimir Chertkov; unfortunately, they have not all survived intact. The A. M. Khir′jakov collection contains 69 letters (seven of these with passages missing), while his wife, E. D. Khir′jakova, preserved 49 (24 of these being additions to her husband′s copies). Pavel Birjukov (1908) selected 23 of these letters for inclusion (in whole or in part) in Volume 2

- xxix -

of his biography of Tolstoy, which were later reproduced in a book compiled by P. A. Sergeenko (1910—11).

Two years later 70 of Tolstoy′s letters to Strakhov were published in a supplement to Sovremennyj mir (1913, nos 1—7, 9—12) and reissued the following year — along with 198 of Strakhov′s letters — as a separate publication by the Tolstoy Museum Society. This new volume included an introduction and annotations by Boris Modzalevskij (1914). While this was one of the most significant editions of their correspondence at the time, most of Tolstoy′s remaining letters to Strakhov (numbering around 200), in addition to all Strakhov′s letters written during the last two years of his life (1894—96), were either still unknown or inaccessible to the Museum Society. In addition, in spite of some excellent annotations by the compiler, the volume as a whole is hopelessly dated, and replete with both factual and textological errors.

In 1922 one letter appeared in the almanac Raduga, and two years later 24 of the letters were published through the Museum Society by Tolstoy′s personal secretary Nikolaj Gusev (1926: 24—64). In Vol. 37—38 of Literaturnoe nasledstvo A. Petrovskij (1939: 151—182) selected excerpts from 26 of the letters which had earlier appeared in the Birjukov and Gusev biographies of Tolstoy. In the 1950s the majority of Tolstoy′s letters to Strakhov were included in Vols. 61—69 (a few appear in Vol. 90) of the Jubilee Edition of Tolstoy′s writings (Polnoe sobranie sochinenij 1928—58) — again, with numerous errors and omissions in the text, dating and commentaries.

One important step toward a more comprehensive understanding of the relation between Strakhov and Tolstoy was my 1999 article on these writers′ unpublished correspondence of 1894—96 which appeared in the Tolstoy Studies Journal, accompanied by twelve of Strakhov′s letters in both their original Russian and an English translation by John Woodsworth. Shortly thereafter the complete collection of letters from 1894 to 1896 letters (24 by Strakhov and 14 by Tolstoy, none of which were included in the Modzalevskij edition) appeared under my editorship (Donskov 2000), as a joint publication of the Slavic Research Group at the University of Ottawa and the State L. N. Tolstoy Museum in Moscow. It also included, for the first time in print, the complete correspondence (1872—1895) between Strakhov and Tolstoy′s wife Sofia Andreevna, dealing chiefly with readings, corrections and the publication of Leo Tolstoy′s works. The volume included brief summaries in English, annotations (in Russian), and my critical introductory essay (in English).

***

Given the scattering of the already published letters across so many editions, as well as the errors and omissions in most of them (see below), it is little wonder that scholars have not infrequently come up with a distorted

- xxx -

and incomplete picture of the dynamic exchange that permeates the length and breadth of the epistolary dialogue between these two deep thinkers.

The topics of this dialogue range from paths of historical development of Russia and the West to the interrelationship between philosophy, ethics and religion to the ongoing careers of both writers — in fact, they cover the whole gamut of cardinal issues under discussion by Russian intellectuals of the period, including what constitutes the Russian mindset, as well as the so-called ′new æsthetic ideas′ characterising late 19th century Russia. The letters provided Tolstoy a canvas on which he could outline his deepest thoughts on the nature of his writings, especially their æsthetic aspects, but these were then developed and refined through subsequent dialogue with Strakhov and can only be fully appreciated in the context of Strakhov′s responses to them.

Another recurring feature of the Strakhov-Tolstoy correspondence is the discussion of both historical and contemporary literary figures, including Karamzin, Pushkin, A. A. Grigor′ev, V. V. Rozanov, Vladimir Solov′ev, Fet and Danilevskij. Strakhov′s references to his readings of Darwin, Spenser and Renan (among others) indicates his broad interest (shared with Tolstoy) in various philosophies, political ideologies and contemporary social issues, although his judgements on such movements as Darwinism, nihilism and spiritualism, as well as the age-old debate between Slavophiles and lovers of Western culture, are, to say the least, highly controversial.

Especially interesting is Strakhov′s relationship to Dostoevsky as revealed in the letters, which indicate a cooling of feelings toward Dostoevsky proportionately to the increasing closeness he felt toward Tolstoy. The sense of anger he so carefully restrained in his published reminiscences on Dostoevsky comes out with full force in his private letters to Tolstoy. This suggests a highly ambivalent attitude in his own thinking, a dualism he may not have been completely aware of himself.28

The compilation of all the letters together in a single series in chronological order is possibly the most salient feature of the present edition, but a number of other valuable contributions to Tolstoy scholarship must also be noted. Significantly, we did not confine ourselves to what had been published before, but carried out an extensive search of epistolary archives in Moscow, St-Petersburg and Kiev for additional letters that had hitherto remained undiscovered — twenty such letters came to light.

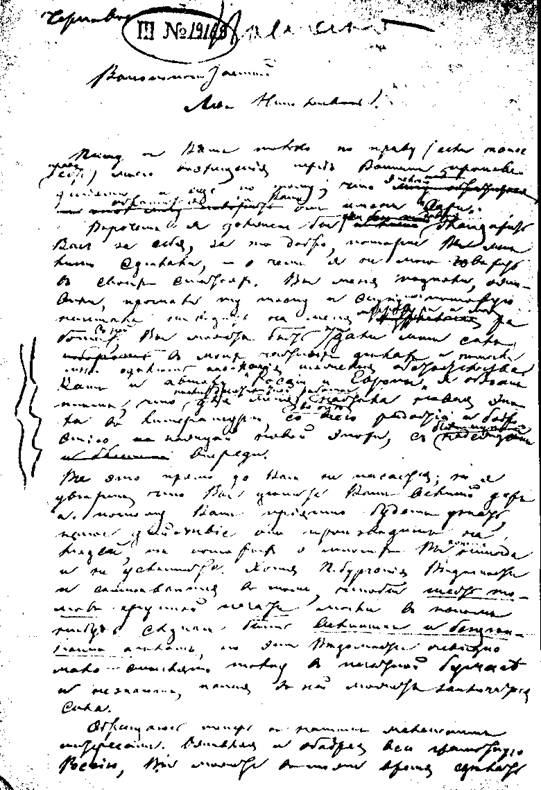

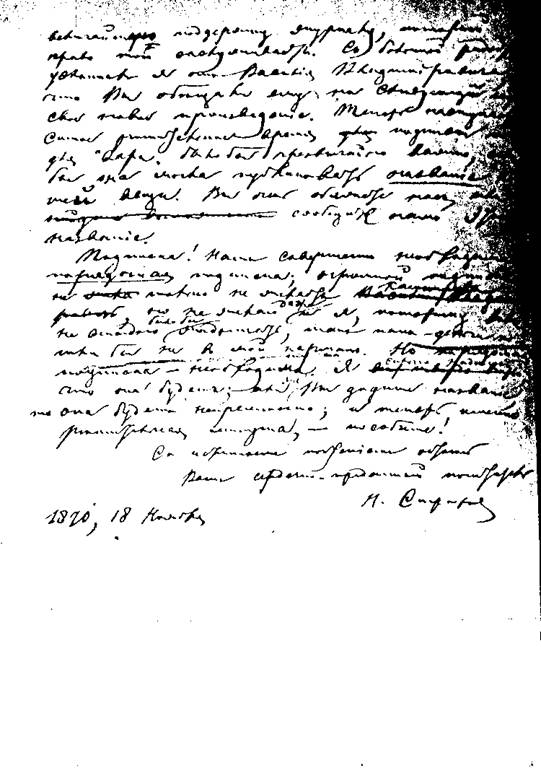

Tolstoy′s second letter to Strakhov (¹ 3 in the present collection, long known to scholars) was written in evident response to Strakhov′s first

- xxxi -

letter to him — a letter which up until just recently was presumed lost. While the whereabouts of the copy actually received by Tolstoy are still unknown, our researches turned up a draft copy among Strakhov′s papers in Kiev29 — complete with crossings-out and corrections in the margins — which is here reproduced as Letter Nº 2, dated 18 November 1870. It is indeed a treasured find, as it gives us Strakhov′s detailed description of how he first discovered Tolstoy through his writings — especially War and peace, on which Strakhov had already published several outstanding articles — and how strongly impressed he had been by Tolstoy′s literary craftsmanship.

Another letter (Nº 436, from the beginning of September 1894) was discovered in the archives of the Institute of Russian Literature (Pushkinskij dom) in St-Petersburg. It is significant in that (a) it contains an outline of one of Strakhov′s disagreements with Tolstoy (on the subject of spiritual versus worldly influences on human development) and (b) Strakhov neither finished nor actually sent it to Tolstoy, much to the latter′s dismay when he heard about it (see Letter Nº 438).

The remaining 18 were found in the Manuscript Division of the L. N. Tolstoy Museum in Moscow.30

While some of these twenty letters had been referred to in quotations in previously published texts, they are presented here for the first time in their entirety, and offer a wealth of new information both for general readers and for Tolstoy scholars. They shed new light on the nature of Strakhov′s views on life, literature and especially Tolstoy, and correct Gusev′s biography of Tolstoy (1960) in providing accurate information about the dates and number of Strakhov′s visits to Yasnaya Polyana and Moscow.

Several of Strakhov′s letters were accompanied by clippings from his articles, which are included here for the first time in relation to the letters.

Next, it is important to recognise that all 467 letters in this collection have been verified against the original manuscripts — a process that has helped fill in a multitude of gaps (both simple oversights by proofreaders and deliberate omissions on the part of censors) and correct earlier misreadings. This edition thus distinguishes itself from many previously published collections based on copies rather than originals, where some letters contain as many as a dozen mistakes or more, if all the minor discrepancies are taken into account. For example:

- xxxii -

È-2. Ïåðâîå ïèñüìî (¹ 2) Í. Í. Ñòðàõîâà…

First letter (Nº 2) written by N. N. Strakhov...

- xxxiii -

…ê Ë. Í. Òîëñòîìó îò 18 íîÿáðÿ 1870 ã.

...to L. N. Tolstoy, 18 November 1870

- xxxiv -

• In the letter (Nº 4) of 13 September 1871 (completely missing in Modzalevskij), Volume 61 of the Tolstoy Jubilee Edition introduces a meaningless word Perog., which should actually read: Ierog. — i. e., an abbreviation of the name of Ieroglifov, a noted Petersburg publisher.

• In another letter (Nº 17), dated 19…20 June 1872, in connection with Strakhov′s checking of Tolstoy′s Azbuka [A Primer] manuscript, Tolstoy gives Strakhov permission to ″throw out anything he finds to be plokhim [bad]″, whereas Vol. 61 of the Jubilee mistakenly represents the word as ploskim [flat, shallow].

• In Tolstoy′s unsent initial letter to Strakhov, dated 19 March 1870 (Nº 1) the following discrepancies were discovered:

Jubilee Edition, Vol. 61

Present edition (as in original ms)

p. 232

neschastnykh b…

p. 2

neschastnykh bljadej

p. 233

Posmotrite zhe

p. 2

Posmotrim zhe

p. 233

u è[toj] zhenshchiny

p. 2

dlja zhenshchiny

• In subsequent letters, similar examples:

Jubilee Edition, Vol. 61

Present edition (as in original ms)

p. 290

pereekhat′ k nam

p. 33

priekhat′ k nam

p. 301

ponadobitsja dlja chtenija

p. 46

ponadobitsja dlja pechatanija

p. 321

Vse perepisyvaju

p. 61

Vsë peredelyvaju

p. 328

napishite takoe zhe

p. 72

napechatajte takoe zhe

It is interesting to note that during the verification process more than 100 of Strakhov′s original letters, which had been missing from the Manuscript Division of the L. N. Tolstoy Museum in Moscow, turned up in the Pushkinskij dom collection in St-Petersburg. They had lain there untouched since 1914, but now, along with other originals, they have served as a primary source for an accurate presentation in the current volumes.

One particular type of inaccuracy that has been corrected in this edition involves chronology — i. e., establishing the date a given letter was written. It has now been determined, for example, that Strakhov′s notations on the original manuscripts of Tolstoy′s undated letters to him reflect the postmark date, i. e., the date the letter was posted and not, as earlier presumed, the date it was received. Taking into account the probability that not all letters were written on their postmark date, we have indicated the range of likely dates of writing by an ellipsis — e. g., a date 3…5 marta would signify a postmark date of 5 March, with the possiblity that the letter might have been actually written on the 3rd or 4th. Some examples of corrected chronological inaccuracies are the following:

• The letter dated January—February 1876 in the Modzalevskij (1914: 73—75) and 1 February 1876 in the Jubilee Edition (V, 62: 243—45) was actually written only after 8 April of that year (Nº 113 in our collection).

- xxxv -

• Vol. 63 of the same edition notes a letter of 1—10? June 1881 as ″not preserved″; the letter is in fact extant, only the date was July rather than June (Nº 280).

Finally, a prominent feature of this new collection is the set of annotations accompanying almost every letter, compiled by Lidia Gromova of the Russian Academy of Sciences and Tat′jana Nikiforova, Senior Researcher with the Manuscript Division of the L. N. Tolstoy Museum in Moscow. A good number of these commentaries are based on Strakhov′s correspondence with many of his other literary contemporaries, including famous names such as Dostoevsky, Turgenev and Fet as well as lesser-known writers like Ivan Aksakov, Dmitrij Averkiev and Mikhail Stasjulevich. In addition, they often draw upon rare periodical materials from the 1870s, 1880s and 1890s.

The annotations are of particular value in shedding light on the creative process underlying the germination, development and publication of many of Tolstoy′s works, in which Strakhov played an active part — Azbuka [A Primer] and its successor Novaja azbuka [A New primer], revised editions of Vojna i mir [War and peace], Anna Karenina, Khozjain i rabotnik [Master and man], among others. He was often the first to read Tolstoy′s new manuscripts. Accompanying a letter of 30 November 1875 (Nº 102) Strakhov received the first draft of Tolstoy′s Ispoved′ [Confession] — showing that the creation of this work dates not from 1877 as is often considered (some scholars have put it even later), but from a significantly earlier date. The commentaries include many details of this sort, as well as excerpts from the draft manuscripts of the works in question.31

***

Personal letters are all the more valuable because of the qualities of authenticity and immediacy not to be found in traditional memoirs. They are addressed to specific people and invite dialogue. While letters may, of course, be used to conceal rather than reveal, no such indications are traceable in the correspondence presented in this volume. On the contrary, being addressed to close personal friends, these letters bear an additional stamp of sincerity. They are marked by a freedom and spontaneity which, like a candid snapshot capturing the momentary now, not only reflect their authors′ personalities but offer a glimpse into their emotional and spiritual make-up — their innermost perceptions on life and art and the interaction between these spheres, as well as the complex patterns comprising the relationships between the individuals involved.

- xxxvi -

Strakhov carried on an active correspondence with many men of letters as well as with members of his family. In addition to his published letters listed in Note 1 above and his correspondence with Sofia Andreevna Tolstaja (Donskov 2000: 131—301), most of the letters written either by or to him remain unpublished.32

Tolstoy was an even more prolific letter-writer. During his long life he wrote more than 10,000 letters and received around 50,000. As Opul′skaja (1990: 5—15) indicates, Tolstoy′s letters are extremely important in rounding out our picture of his personal life — his loving relationship with his wife and their eventual separation is shown in his correspondence with family members, his epistolary exchange with Vladimir Chertkov and his aunt Aleksandra Tolstaja elucidate his views on the evolution of his moral-religious philosophy, while with the poet Afanasij Fet he discussed issues of poetics. This latter emphasis on burning issues of the intellect marked a break from the content and style of letter-writing of Pushkin′s day. In the latter part of the century, even though there were still ephemeral references to mundane topics (the weather, family affairs, the planning of meetings and visits etc.), the focus became even more concentrated on deep social and political issues, including criticism of government policies and religious officialdom, not to mention significant moral and ethical questions, ultimating in an ongoing discussion of the meaning of life and man′s place in the universe.33

Perhaps the most significant aspect of the contents of the letters for Tolstoy scholars, however, is the fresh insights they provide about the major works Tolstoy and Strakhov were producing over the quarter-century between 1870 and 1896. They help explain and clarify not only the aims of the novels and treatises, but also the practical procedures involved in their publication and their reception on the part of contemporary critics. Strakhov was endowed with a sensitive insight into the writer′s thought-processes, which he himself acknowledges in one of his letters to Tolstoy (Nº 60): ″having almost no creativity, I do have a rather large capacity for understanding″. Tolstoy, too, confirmed this perception on more than one occasion.

The letters record the whole history, for example, of the enormous contribution on both the technical and content level that Strakhov made

- xxxvii -

to the editing and publication of Tolstoy′s Azbuka [A Primer],34 — a contribution for which its author was most grateful. The letters thus confirm the impression evident in a comparison of corrected texts with the original and give the lie to the lingering rumour among Soviet-era scholars that Strakhov′s assistance to the writer was confined mainly to proofreading and correction of punctuation. For example, in Letter 27 of 15 September 1872, Tolstoy writes to Strakhov as follows:

As far as the distribution of the Slavic [texts] are concerned, do as you propose. As to [the chapters on] gases and heat [I] am in agreement, and I leave it up to you to do as you wish. [italics mine — A. D.]

Two weeks later (in Letter 29 of 29 September 1972) Tolstoy issues a directive in a similar vein:

I am in complete agreement with the dimensions you propose for the books. … It would be very good to include a note and list of errata at the end.

In 1873 Tolstoy enlisted Strakhov′s assistance in revising his first major novel, War and peace. The following excerpt from Letter 48 (of 25 March 1873) typifies not only the content, but also the tone of Tolstoy′s many queries for Strakhov′s advice:

One further request: I have begun to prepare War and peace for a second edition and to cut out anything non-essential — [to decide] what needs to be deleted entirely, and what needs to be taken out for book publication. I should appreciate your advice, if you have time to look at the last three volumes. And if you can remember what isn′t that good, remind me. I′m afraid to touch it, since there is so much that isn′t good in my view that I almost feel like re-writing the whole thing from the start. If you could remember what needs to be changed and look over the last three volumes of the text, and say that such and such needs changing and the whole text from page so-and-so to page so-and-so needs to be thrown out, I would be very, very much indebted to you.

A year later Tolstoy sent a draft copy of his article ″O narodnom obrazovanii″ [On public education] to Strakhov; the accompanying letter (Nº 73, dated 19…20 June 1874) contained the following request:

I finished the article; it turned out to be quite long, and as I was writing it I wanted very much to have it published, but now I myself don′t know how meaningful it is, as I have been busy with other things. Here is my request: read it over with a pencil in hand for crossings-out and tell me whether it is worth publishing, and where?

- xxxviii -

Tolstoy subsequently sent this article to Nikolaj Nekrasov, editor of Otechestvennye zapiski, with the notation (PSS 62: 110):

…I urge you to have the proofs sent to Nikolaj Nikolaevich Strakhov … and accept any changes he makes as my own.

Tolstoy continued to have a high estimation for Strakhov′s talents as a critic. When it came time to work on Anna Karenina it was to Strakhov that he turned for help, in his letter (Nº 112) of 8…9 April 1876:

Every writer has his atmosphere of worshippers which he carefully carries about him and can have no idea about his own significance or about his times of failing… I would not want to go astray myself… Please help me with this.

Strakhov always heeded Tolstoy′s requests most conscientiously. His comments to Tolstoy were characterised by accuracy and meticulous detail, not only about the various instalments of Anna Karenina but also concerning many subsequent works. In addition, he regularly passed along to his mentor comments on Tolstoy′s works from other writers — e.g., Danilevskij, Stasov, Aksakov and Polonskij.

Yet his loyalty to Tolstoy, as we have seen already in glimpses, by no means prevented him from balancing his praise of the writer′s genius with honest criticism where he perceived a need for it, with the full knowledge that Tolstoy expected no less of him. At times this led to serious disagreement — for example, in their differing attitudes to the ′eternal/temporal′ dichotomy that frequently pervaded their discussion (see, for example, Letter Nº 434 of 18 August 1894).35 But at no point did their disagreements degenerate into uncomprising arguments; rather, they were mitigated by a deep and sincere respect for one another, and whatever ideological conflicts that surfaced during their discourses (either oral or written) were heavily outweighed by an overall spirit of mutual attraction.

It is perhaps this overall sense of unity between the two men that allowed Strakhov to feel free to disagree at times — and even argue — with the mentor for whom his admiration otherwise knew no bounds. Indeed, it is evident that his arguments did not stem from a sense of self-aggrandisement (unlike some sectarians who thought of themselves as Tolstoy′s equal, Strakhov was far from flattering himself as

- xxxix -

a prominent expert on truth or a teacher of life). Even as he gave due recognition to the monumental scale of Tolstoy′s nature and talent, he still retained the right to his own ′free will′ and sense of judgement in the face of this overwhelming personality. This makes Strakhov′s own opinion all the more interesting, and it is not surprising that it was so highly valued by Tolstoy himself.

***

It will be useful to look at a few examples of both favourable and negative reaction to Tolstoy′s works on Strakhov′s part. In Letter Nº 57, dated ″after 3—4 September 1873″, in response to Tolstoy′s request for comments regarding his article ″Voprosy istorii″ [Issues of history], Strakhov allows a degree of praise but is also forthright in pointing out its weakness. He proposes, for instance, throwing out the final paragraph comparing revolution in history with Copernicus′ revolution in astronomy, describing it as not coming up to the standard of ″amazing accuracy and clarity″ characterising the rest of Tolstoy′s article. He also takes issue with Tolstoy′s extension of the term historical events to cover such actions as getting angry or giving orders.

Strakhov had generally high praise for Anna Karenina, a work he found remarkable for its ″amazing freshness″ and ″utter originality″ (Letter Nº 75, dated 23 July 1874). Later in the same letter he comments:

As far as I am concerned, the inner story of passion is the main theme and explains everything. Anna kills herself with the egotistical thought of serving the same old passion; it is the inevitable outcome, the logical conclusion of the direction indicated right from the beginning. Oh, how powerful, how compellingly clear!

His praise continues in subsequent letters. In Letter Nº 82 (8 November 1874) he finds Levin′s confession of love particularly charming, along with the scholarly conversation involving Levin′s brother: ″All this is fresh, new and infinitely true and refined!″, although he finds the conversation in the tavern ″rather long″.

In reporting to Tolstoy both positive and negative reactions to the novel by journal commentators and his personal acquaintances, Strakhov finds himself in agreement with at least one major criticism. He explains it this way in a letter (Nº 161) of 8 September 1877:

Among the criticism levelled at you, only one of them makes sense. The critics have all noted your reluctance to dwell on Anna Karenina′s death. And you told me yourself that you have a hard time coping with this particular tragedy. I still don′t understand the feeling that is controlling you. Perhaps I shall makes some sense of it, but help me. Your latest variant of the death scene was frightfully dry. Besides, I don′t think it′s a good idea to offer the reader a new version when all the details of the earlier one, right down to the last, are already etched in their memory. I shall send

- xl -

you both versions re-copied and, even though I hate to bother you and interrupt your current work, would ask you to consider once more whether we shouldn′t forget about the second variant?

Another point of disagreement was Tolstoy′s not infrequent tendency to expound on the moral lessons of his stories at the expense of their artistic and entertainment elements, coupled with an ascetic rejection of important human values (as Strakhov perceived them) embodied in philosophy, poetry and the arts. Strakhov, himself a strong Russian nationalist to the end, could not bring himself to accept Tolstoy′s categorical denial of patriotism.

An example of Strakhov′s objections along this line is found in his fascinating letter to Tolstoy (Nº 319) of 26 October 1885. Setting out what might be considered his own ′artistic credo′, he criticises what he sees as Tolstoy′s excessive moralising in his fairy-tale Skazka ob Ivane durake i ego dvukh brat′jakh: Semene-voine i Tarase-brjukhane i nemoj sestre Malan′je i o starom d′javole i trekh chertenjatakh [The Story-legend about Ivan the Fool and his two brothers: Semyon the warrior and Taras the Fat-bellied and their mute sister Malania and the three little devils]. The passages reproduced here in English translation offer one of the most comprehensive insights into Strakhov′s view of literary art.

I have read two of your new pieces: a letter to Kh. Kh. [i. e., M. A. Èngel′gart] and a fairy tale. The clarity, feeling, power and sincerity of the letter made me ecstatic, but the story saddened me to such an extent that I walked around for two days in a wounded state. I never judge a work on the basis of whether I agree with it or not. But when I perceive a feeling, a work of intellect, creativity, even anger or blatant sensuality, I am happy, because here before me is a phenomenon of life which suits me — I need only be capable of putting it to good use. But when I am faced with a composition, verse without poetry, a picture without a painting, a fairy-tale without fairy-tale content, then I see before me something manufactured, unnatural, contrived, pieced together with a mask of life applied to it, and I can only be annoyed at the senseless waste of energy, at the use of base means to fulfil noble aims. You are such an amazing artist, you have no justification to write that way. Patent moralising and rationalising — is something marvellous, and a short witty piece like an &Aelig;sopian fable is fine, but a long story — that should be a work of art….

Patent moralising in a story is bad because it goes against the whole rationale of a story, it makes even the best story into something false and contrived and takes away from its sense of naturalness. The second half of your fairy-tale has no thematic thread, no living beings, no living scenes. And the content — i. e., the didactic themes you introduce — sticks out in huge clumps, enough for twenty such tales. And the lack of artistic development makes for inaccuracies. You argue that one cannot get by on the basis of the state, war or commerce, yet France, England and Germany get by; you write that an enemy would quit a peaceful country, yet the English have no intention of quitting India. The enemy has taken

- xli -

over the land, turned the local inhabitants into slaves, and so forth. In a word, there is a multitude of topics here that have already come to realisation in history, and their absurdity needs to be brought out with great precision.

But the main thing is — forgive me, dear Lev Nikolaevich — that the evidence will not stand up to criticism. Your supreme argument is happiness, well-being. But I don′t think it proves anything. Everyone chooses happiness in his own way, and even if you show that it is a holy thing to suffer and that it is more blissful to die than to live a long rich life with sins large or small, you will not prove anything. Salvation of the soul — now that′s the only true bliss. Virtue is its own reward, as the dictum goes.

In subsequent letters, however, Strakhov followed his typical pattern of recanting his criticism and asking for Tolstoy′s forgiveness for his outburst, even attempting to counterbalance it with self-condemnatory remarks about his own character and philosophy.

Tolstoy, for his part, was equally concerned about offending Strakhov′s feelings by his own sometimes forthright criticism of his correspondent. This mutual concern for each other′s sensibilities, which permeated their entire epistolary exchange, is well illustrated in the following paragraph with which Strakhov begins his letter to Tolstoy (Nº 190) of 25 April 1878:

You are greatly mistaken, precious Lev Nikolaevich, if you think that you upset me, blaming yourself and supposing that I could become angry at you. No, that is impossible. The tone of my letter was wrong if such thoughts could come to you. In view of the deeply serious nature which I see in you and love with all my heart, I could not find any fault in you; even if you should pass the severest possible condemnation upon me, I would only look within myself for the causes for such condemnation. And now, since you have spoken to me only something ambiguous, the only thing I can accuse you of is an excess of sensitivity.

Strakhov′s comments on Tolstoy′s play Vlast′ t′my [The Power of darkness] are equally revealing of his fine critical acumen. In his letter to Tolstoy (Nº 333) of 27 January 1887 he hails the first act for its fresh and pure artistic impression, but then quickly goes on to point out a weakness — namely, that the subsequent acts fail to hold or develop the interest of the viewer. The characters remain static, especially Nikita, whom Strakhov finds poorly drawn and his repentance unconvincing; the audience is not shown how Nikita′s conscience awakens with the realisation of his sins. Strakhov concludes: ″The drama evidently lacks integrity, there is not a single node of gradual development.″

To support his position, he cites Ostrovsky′s Grekh da beda na kogo ne zhivet [Sin and sorrow are common to all], which he considers ″irreproachable in its structure″:

- xlii -

Everything in it just rolls along, entertaining the audience, and inevitably leads to the final blow. Such a structure immeasurably enhances the significance of each and every scene, each and every detail.

Strakhov begins his very next letter to Tolstoy [Nº 334], however, with an attempt to soften this rather harsh criticism with an apology:

I feel very ashamed before you, precious Lev Nikolaevich; in my zeal I was too hasty and showed great lack of restraint in writing you my judgement on your drama. I am now very angry at myself…

Not only does he, in effect, retract his earlier criticism, he goes to the other extreme and praises the work in the most glowing terms (″What charm! What perfection!″). He does add one caveat, however, but only with considerable restraint:

I see in the drama two or three bad spots — but now I shall be smarter, I shall not talk about them until I have taken a better look and given them some careful thought.

It may be noted how the force of Strakhov′s direct challenges to Tolstoy was mitigated both by his unflagging loyalty to his mentor and by his own innate proclivity toward moderation in all things — except, perhaps, for his all-too-frequent expressions of that loyalty. He could not close the above-quoted letter without adding one more commendation:

Nevertheless, above all, forgive me for imposing myself upon you with my letters. Today′s letter, as you can see, was altogether necessary, apart from my constant desire to assure you of my unswerving loyalty, in which I bow before you in profound reverence.

Far from feeling angered or insulted by Strakhov′s challenges, Tolstoy ultimately respected his friend for his frank and sincerely expressed views. It must have been evident that Strakhov differed from the general run of Tolstoy′s admirers who were either unwilling or unable to discern and point out places in his writings that needed improvement as well as from the writer′s many literary foes who were either unable or unwilling to see much good in his writings at all. Confident in Strakhov′s unwavering, underlying appreciation of his position as a leading thinker and critic, Tolstoy trusted his associate to provide an honest appraisal and, more often than not, accepted and acted upon his advice. A significant proof of this trust may be seen in the fact that in January 1895 Tolstoy sent Strakhov his initial draft of Khozjain i rabotnik [Master and man], asking him to take charge of its proofreading. But even more telling was Tolstoy′s second (and more humble) request (in Letter Nº 442 of 14 January 1895):

Take a look at it …, and tell me whether [you think] it is … worth publishing. Isn′t it shameful? It′s been so long since I have written any kind of fiction that I really can′t tell what has turned out… If you think the story

- xliii -

worthy enough, then please sign the proofs [and forward them] for publication.

The remainder of the dialogue concerning Master and man is one of the most enlightening parts of the whole correspondence (see Letters 442—448 and 453), and bears further study, especially as it leads into a whole discussion revealing the two thinkers′ differing approach to philosophy, as well as Strakhov′s extreme penchant for editorial perfection, in contrast to what he perceived as Tolstoy′s apparent disregard for it. For example, in Letter 427 Tolstoy comments on Strakhov′s article on the history of philosophy as follows:

I was just remembering the end of your article — the story of how philosophy died out for forty years and was then revived by Helmholtz. Well, there is something unreal about any philosophy capable of dying out and coming back to life.

Strakhov replies in Letter 430:

You say philosophy is not all that essential if it was neglected for thirty years. But as I stated, I was talking about facts, about history. And actually an important point in my article is still missing — what effect philosophy has had and still is having on people′s lives.

Note Strakhov′s correction of Tolstoy′s inaccurate reading of the article, restoring ″thirty″ for the latter′s mistaken ″forty″ and his original ″neglected″ for the misread ″dying out″ (the latter would imply the existence of some inherent cause for its demise). Such a comparison of the two points of view is one more benefit of publishing this correspondence in full.

Perhaps the core of the Tolstoy/Strakhov disagreement is best revealed in the ′moral-religious′ discussion in Letters 434—439. Following his return from Yasnaya Polyana in August 1894, Strakhov wrote to Tolstoy (Letter 434):

You are doing a great work at Yasnaya Polyana, and are attracting splendid people there! I felt like simply giving in to the euphoria I felt at this scene, just learning all sorts of virtues. But you know what I am concerned about. I don′t know how to reconcile this striving for the eternal with the temporal. Renouncing the world inevitably leads to a denial of the world. … There was a lot of talk at Yasnaya Polyana against the State, patriotism, industry, science, music, poetry, philosophy etc. All of those things are, of course, superfluous from the point of view of the one thing needful;… But they are all what people live by, and will live by.

Here Strakhov had perceived the very weakest point in Tolstoy′s philosophy — namely, the inevitable demand for some kind of sacrifice or denial, bordering on nihilism, from which it differed only in that the sacrifice was for a good cause. Strakhov was very exacting in his use of terminology: Renouncing … leads to … denial. In other words, defending

- xliv -

one′s self against the world′s imperfections may eventually turn into aggression directed against the world. In this formula of Strakhov′s there is hardly anything anyone can object to. Nor did Tolstoy object in his response.

One significant gulf between the two correspondents centred around the reconciliation of religious belief with rationalism. For Tolstoy faith in a higher being was paramount, while for Strakhov it was subject to the parameters of human logic. The conflict is illuminated in Strakhov′s still unpublished correspondence with one of Tolstoy′s critics, Ivan Sergeevich Aksakov, in which he allowed himself a greater degree of frankness than in his letters to Tolstoy. In a letter of 12 December 188436 he writes in a still restrained tone:

Everything Tolstoy writes concerning his subjective interpretation of Christianity is very poorly written; but his feelings, which he is entirely unable to put into words but of which I have direct knowledge through his facial expression, his tone of voice, his conversations, are imbued with a beauty all their own. There is so much of everything in him; but I am struck, and forever will be struck by his character, the Christian traits of his character.

However, upon re-reading Tolstoy′s Kratkoe izlozhenie Evangelija [The Gospel in brief] (the particular reference in the above quotation), he launches into a much more scathing attack on Tolstoy′s position. His letter to Aksakov of 17 May 1885 is so important that it is worth quoting almost in its entirety:

On holiday here in Mshatka I read over the whole Gospel in brief with complete attention (and comparison with the [Scriptural] text) and, I must confess, despite my usual position regarding Lev Nikolaevich Tolstoy, I was astounded at the utter hideousness of the writing. It had seemed to me that he would have clung even closer here to his own translation of the Gospel text — the translation I am familiar with, which he keeps at Yasnaya Polyana. As it turned out, his Gospel in brief goes beyond all bounds in its departure from the text, that it is not even a translation but some kind of paraphrase, just like the content summaries at the beginning of each chapter [of the Gospels]. The whole thing gives the appearance of distortion and deception. These utterly gratuitous departures, by their sheer numbers, take away from those places where there is no departure from the actual text but only from the generally accepted translation, which are indeed precise and significant.

The language is unrestrained, uneven, and sometimes unnecessarily crude. ″Who knocks a tooth out of one side of your mouth, turn to him the other also″37 — that′s how the familiar rule is worded. A simple insult

- xlv -

has been replaced by a physical wounding — apparently out of a passion for powerful and vivid expressions rather than for clarity′s sake.

Further, the headings do not correspond with the content; it is not clear what the division into chapters is based on; the sequencing is most obscure; there are endless repetitions; the expression of thoughts and their interrelationships shows neither firmness nor accuracy. In a word, it is an outline that is good for nothing and does more to obscure [the text] than explain it.

Still, in its essence and in relation to the Gospel text there is something precious, even priceless, here. Christ′s practical teachings are understood quite correctly, and even his theoretical doctrine, I think, is comprehended accurately in some aspects, or at least more accurately than usual. There are some translations which bring out the meaning remarkably — for example … teachings rather than words. The whole Sermon [on the Mount] takes on a straightforward human tone, which it undoubtedly had in reality, and for this reason the interpreter was more inclined to use crude language rather than fall into a superhuman majesty which places an enormous gulf between us and the Gospel sermon. If the kingdom of heaven is capable of being established within us, then its sense ought to be expressible in terms of our everyday speech. There is nothing more harmful than imagining the divine to be something special, to think that it is far removed from us and cannot be something close by. In that case we are condemning ourselves in advance to a life apart from Deity, and so we live that way; we content ourselves with lofty words and images; we look upon the deeds as impossible.

Tolstoy has brought out some very important and altogether correct sequences and relationships in the Gospel text, for example, his pointing out of the five little commandments, his interpretation of the parables, his discussion of the Last Supper and the last discourse of Christ, and so forth. It is a pity that sometimes these pearls get sunk in some kind of muck.

Then, in the dogmatic sense, of course, he is a huge heretic; in terms of practical teachings he is a Quaker and in terms of the metaphysical he′s a Unitarian.

Strakhov continues in a postscript:

I forgot to mention an important point, concerning the position of falsity in which Tolstoy has placed himself, to some extent inadvertently, although in part deliberately. Since he does not recognise miracles or revelation, he naturally cannot recognise the indisputable meaning behind the letter of the Gospel. Moreover he spares no effort trying to prove that this letter has the sense he desires — in other words, he does things which are completely unnecessary, and does not do the things he should do. Looking at it from another angle, one could say that he is carried away by the spirit of contradiction, by the desire to show Christians that they are not confessing true Christianity. On the positive side, however, one could conclude that he cherishes immeasurably a sense of harmony between his thoughts and Christ′s teachings, and therefore stubbornly seeks their expression in a text he himself cannot bring himself to regard as entirely

- xlvi -

trustworthy. He argues, in essence, that much more of the true teaching — i. e., the teaching he has found within himself — has been preserved in the text than is apparent, or than people think. (This teaching is not new, but eternal through the ages.) In any case he (unforgivingly) leads the reader astray from the true standpoint and into a virtually inescapable state of confusion.

Again, forgive me if this long letter has only served to comfort myself and not you.

All of this may be seen as part of the fundamental difference between Tolstoy′s faith- and spirituality-based world-view on the one hand and Strakhov′s more humanistic, rationalistic approach on the other. While Tolstoy inevitably stressed the moral and spiritual dimension in natural beauty,38 Strakhov saw the wonders of nature in an inseparable relationship to humanity′s appreciation of them. This is expressed most vividly, perhaps, in his book Mir kak tseloe [The World as a whole] (1872), a compendium of earlier published scholarly articles. On this occasion, however, Tolstoy was unstinting in his praise, telling Strakhov in the first part of a letter (¹ 44) written 12 November 1872: